Vancouver’s East End, roughly the area of today’s Strathcona neighbourhood, gained its reputation as a slum area early on. In February 1918, a committee of the Board of Trade toured the area and found that the dearth of building regulations was allowing slum quality housing to proliferate in this part of town. Some of the buildings “have plenty of air now because no buildings are on either side,” the committee reported, but these would inevitably become “dangerous disease breeders, with their small light wells and their insufficient ventilation.” The rate of tuberculosis infection was already rising in the area and the government was spending “a considerable sum of money combating the disease.”

The Board of Trade committee’s warning went unheeded. Twenty years later, the jury in a 1939 murder trial toured the scene of the crime, “the premises known as ‘Hogan’s Alley,’ 200 Block Prior Street, ‘Park Lane,’ and 1022 Main Street, etc.,” and found there “hovels utterly unfit for human habitation.” The jury concluded that such conditions were conducive to the crimes carried out by the “degraded humanity … which emanated from these dirty hovels.” With support from Judge Aulay McAulay Morrison, the jury conveyed its consternation in a report urging immediate government action. “If these places were wiped out, as they certainly should be,” the jury surmised, “probably one half the trials, one half the time and grief, and one half the public expense of this year’s Spring Assizes would have been saved.” If the legal authority to carry out the “total destruction and elimination of these places” did not exist, the report argued that “it should be created and used.”

The jury wasn’t completely unsympathetic to the “dregs of humanity who are herded in such a terrible squalor in our midst.” By objecting to the court’s invasion of his home, one “British subject” showed that “even in ‘Hogan’s Alley’” there existed “something good – some pride of citizen-ship, something worth saving.”

Meanwhile, the city’s first female alderman, Helena Gutteridge, was leading an energetic campaign for social housing. She frequently referred to the jury’s report in the weeks following its release, and added that her housing committee could add to their assessment “a hundred-fold” from its probes into other areas. But, she said, in making the case for a federally funded social housing scheme, “it must be realized demolition of such habitations would drive their owners into tents. It would be futile for the city to initiate a drive against shacks and cabins until arrangements had been made to locate their inhabitants elsewhere.”

City officials who toured Hogan’s Alley in response to the jury’s report drew the same conclusion. In their report back to city council, they stated that while it was understandable for outsiders to be appalled that the deplorable living conditions in the East End were allowed to exist, the “lack of suitable low cost housing accommodation” in the city made the wholesale demolition of slums unfeasible. Instead, they recommended that government “housing schemes be given every facility and consideration as it is felt the only remedy lies in this direction.”

The police, meanwhile, laughed “at the thought of the city’s centre of crime being one small lane [Hogan’s Alley].” Chief Constable Foster noted that “there are many people in the alley who are just poor – not criminals. Others, of course, we are called in to deal with.” The Province article reporting on Hogan’s Alley conditions also noted that many of the serious crimes that gave the alley its reputation did not actually take place there. Still, the Province insisted, “Hogan’s Alley has the name which conjures up images of bootleggers, canned-heaters, prostitutes, and all types of criminals” and was “representative of the district in which it is located, a district of tenements, cheap hotels, cabins and tumble-down houses, which extends for blocks around.” In other words, Hogan’s Alley was the Main and Hastings of its day and the East End had the notoriety of its successor, the Downtown Eastside.

Carl Marchi, a bootlegger known as “the mayor of Hogan’s Alley,” pointed out to the Province reporter that many of the so-called hovels were in fact well maintained, and that the alley’s bad reputation was no longer justified. In fact, a 1939 investigation into bootlegging showed that Marchi’s place at 251 ½ Hogan’s Alley was the only bootlegging joint still operating in the alley. A Vancouver police list of the “most aggressive bootleggers” had only one entry for this area – 209 Union Street – and most were closer to Granville. Marchi did agree, however, that some places should be either restored or pulled down.

Both slum clearance and social housing schemes would have to wait until after the war, when Vancouver’s perennial housing crisis affected returning veterans in addition to the traditionally under-housed poor. Nevertheless, some demolitions went ahead in 1939. Newspapers reported that at least two buildings in Hogan’s Alley were to be demolished as a result of the jury’s report. The city’s medical health officer admitted “he could not really say the cabins are in themselves a health hazard, although persons living there were bound to have a lower mental outlook with less desire to improve themselves.”

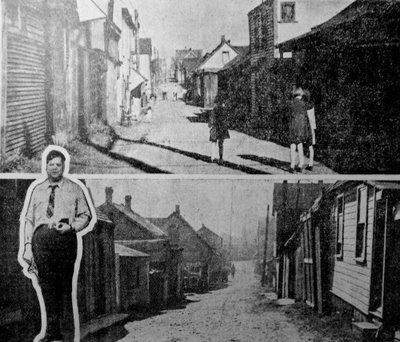

These three cabins survived the Great Fire of 1886 only to be demolished in the 1930s. City of Vancouver Archives REF. # GF N5.2

The two structures were likely part of this trio of historically significant cabins located at 217, 221, and 225 Prior Street that were torn down that year. They survived the Great Fire that levelled Vancouver on 13 June 1886. According to Fred Sanders, son of Edwin Sanders, the contractor who built them, fifteen people found refuge in each of the cabins the night of the conflagration. The Province reported in 1935 that they were “comfortably habitable after fifty years … [and were] a sturdy tribute to the durability of British Columbia timber.”