Al “Cappy” Hubbard was a mysterious fellow. His life was certainly fascinating, even extraordinary. Inventor, spy, adventurer, sea captain, pilot, doctor, snitch, and eccentric millionaire were all on his resume, but he is best known as the “Johnny Appleseed of LSD.”

Born a poor Kentucky hillbilly, Hubbard first found fame in Seattle in 1919 as the boy inventor of a coil contraption that, according to the Post-Intelligencer, generated electricity with no apparent power source.

Al Hubbard’s relationship with Vancouver probably began while working for millionaire George Reifel’s rum running operation in the 1920s. Hubbard operated a wireless shore-to-ship communications system out of a phony Seattle taxicab, allowing the rum fleet to stay one step ahead of the police and coast guard. He was eventually pinched for this and after an 18 month prison stint switched sides and began helping the US government stem the flow of illicit booze.

During WWII, Hubbard’s talents were utilized to secretly transport American ships and planes into Canada to aid the British war effort in the days before the US officially entered the fray.

Little is known about his work with the OSS during the war, but in a September 1980 article in Vancouver Magazine, Ben Metcalfe claimed that Al Hubbard had once shown him “photographs of himself accompanying the American-Canadian party into Port Radium to pick up the first shipment of uranium for the Manhattan Project.”

Hubbard settled in Vancouver after the war and became filthy rich. He drove a Rolls Royce, bought a Gulf Island, and owned a big yacht and a small fleet of airplanes. His riches were apparently derived from a company called Marine Manufacturing and perhaps from his role as the Scientific Director of the Uranium Corporation of BC Ltd.

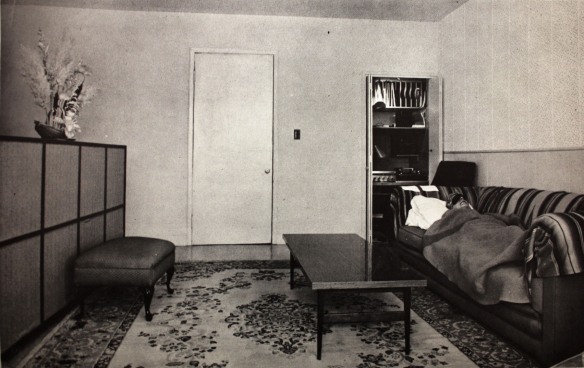

Strengthening the theory that Hubbard continued his spy career with the CIA after the war (which he emphatically denied), these endeavours seem to have been as sketchy as his espionage and criminal activities. For instance, the mailing address of the Uranium Corporation was 500 Alexander Street, a residential building originally built as a brothel and now a skidroad rooming house – hardly an address befitting an important sounding company or its millionaire director. In any case, Hubbard’s wealth enabled him to pursue his true passion: turning people on to LSD.

After his first acid trip in 1951, Hubbard was sold. He contacted Sandoz, the Swiss pharmaceutical company that discovered LSD, and became its main North American distributor. He soon became known as the “Johnny Appleseed of LSD” supervising literally thousands of acid trips and supplying others to do the same.

Hubbard became a doctor by purchasing a degree in biopsychology from a Tennessee diploma-mill. In 1957, he teamed up with Dr J Ross MacLean who had recently taken over Hollywood Hospital, a private mental health facility in New Westminster. Hubbard already had years of experience supervising acid trips under his belt, including those of Aldous Huxley, Vancouver Sun publisher Don Cromie, and Reverend JE Brown of the Cathedral of the Holy Rosary.

Cathedral of the Holy Rosary, 646 Richards Street. Hubbard convinced church leaders that LSD had great potential for enhancing the religious experience.

1957 memo to parishioners of the Cathedral of the Holy Rosary about the religious possibilities of LSD. (Click to enlarge)

Although mainly associated with hippies and evil CIA experiments, LSD was born out of the same pharmaceutical revolution that rejuvenated the profession of psychiatry and gave us antidepressant and antipsychotic medications. In the 1950s, LSD was largely still the fodder of researchers and scientists, not the freaks and dropouts who later claimed it as their own.

Thanks to Hubbard, Canada was already a top centre for LSD research. A 1953 meeting at the Vancouver Yacht Club with Dr Humphrey Osmond (the man who coined the term “psychedelic”) resulted in Saskatchewan becoming one of the top LSD research centres in the world. Osmond relocated from Britain to take advantage of the supportive environment for experimental medical research in Saskatchewan under the Tommy Douglas government. Hubbard contacted Osmond after hearing about his work in exploring the potential of mescaline to better understand schizophrenia.

Hollywood Hospital carved out its niche by using LSD to treat alcoholism. The initial hypothesis was that an acid trip would be akin to the delirium tremens that alcoholics suffered when hitting rock bottom. Researchers instead found that alcoholics benefited from LSD, not by inducing rock bottom, but because the experience heightened their awareness of themselves and gave them insight into the nature of their problems.

The Acid Room at the Hollywood Hospital. The setting was considered very important in LSD therapy at the hospital. The room featured a state-of-the-art hi fi system, a strobe light, and a print of Salvador Dali’s Crucifix. Photo from J. Ross MacLean et al, “LSD-25 and Mescaline as Therapeutic Adjuvants: Experience from a seven year study,” January 1965 (Vancouver Public Library)

Although there was some criticism and debate concerning methodology, LSD therapy proved an impressive remedy for 50 – 80% of the people seeking treatment for alcoholism. Another interesting finding to come out of Hollywood Hospital was that while LSD failed to cure homosexuality, it was beneficial to homosexuals trying to cope in a heterosexist world:

Few homosexuals in our group have attained a satisfactory heterosexual adjustment, yet many have derived marked benefit in terms of insight, acceptance of role, reduction of guilt and associated psychosexual liabilities.

The same report also notes that LSD was attractive for non-therapeutic purposes:

Although the patients reported in this paper all had clearly identifiable personality or behavioural problems, ranging from the mildly disturbed to the acutely ill, a growing number of ‘normals’ are seeking the benefits often derived from a psychedelic experience. For this group, and to some extent for our patients, the term ‘therapy’ is perhaps not entirely appropriate.

In 1957, a Province reporter named Ben Metcalfe arrived at Hollywood Hospital looking for missing-in-action Socred Forestry Minister Robert Sommers. It turned out that Sommers and many other high profile people sought treatment at the hospital, including Cary Grant, crooner Andy Williams, and Robert Kennedy’s wife Ethel. For Metcalfe, it was the beginning of a long friendship with Al Hubbard.

Metcalfe returned to Hollywood Hospital in 1959 and dropped acid under Hubbard’s supervision for a series of articles published in the Province newspaper in September 1959.

Besides taking LSD himself for the assignment, Metcalfe observed sessions of patients and interviewed test subjects. One Vancouver woman quit heroin after a 3½ year addiction, and others had given up alcohol. According to Metcalfe, the treatment was “the most dramatic experience made accessible to the human mind.”

Besides uncovering all the old wounds of the mind, the traumatic areas of fear, shock and guilt, it seems to reveal to the patient that he alone is responsible for who he is and what he will be. He learns to accept this. This period of acceptance of reality on a practical basis lasts for several months. “It is during this time when the patient can practice on the truth,” Dr. MacLean says. “He or she is relaxed at last, they have seen a great deal that is true about themselves and their relationship with others. Now they can work at it.” This is the real cure period.

Metcalfe later recalled that his articles “stood this town on its ear.” Notably, they riled Dr James Tyhurst, the head of the BC College of Physicians and Surgeons and the Psychiatry Department at VGH. Tyhurst had been trying to have Hollywood’s funding cut and claimed that he could induce the same effect on the mind using only salinated water.

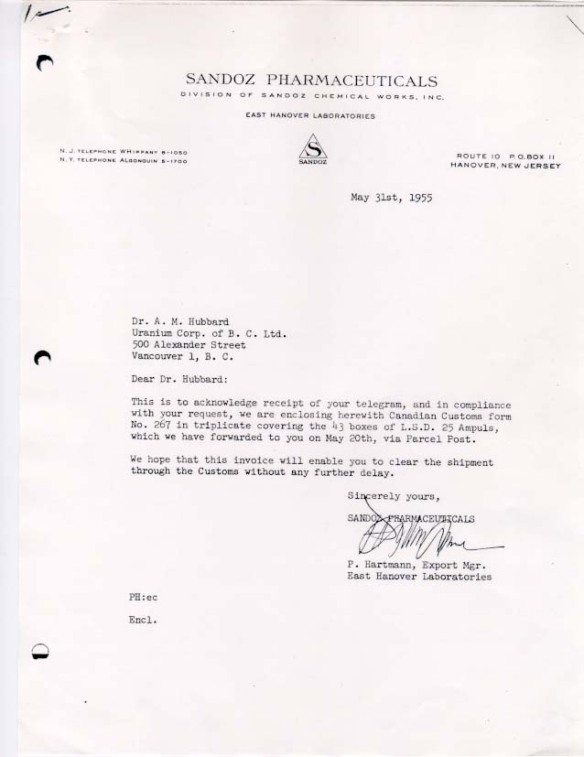

Letter to Dr AM Hubbard from Sandoz Pharmaceuticals regarding the shipment of 43 boxes of LSD ampuls. Later the same year, Hubbard provided Aldous Huxley with his first dose of LSD. (click to enlarge)

Tyhurst’s goal of having Hollywood Hospital shut down wasn’t realized until 1975. By then, LSD’s reputation had shifted from being a new pharmaceutical with exciting therapeutic possibilities to a street drug corrupting our youth and driving them insane. Leading the crusade against LSD in Vancouver was Pat McGeer, a UBC brain researcher and Liberal MLA for Vancouver-Point Grey.

In a 1967 speech to the legislature, McGeer demanded that university professors and school teachers who advocated the use of the drug be immediately fired. “Contrary to the opinion of pseudo experts,” he said, “LSD does not expand the mind but shrinks it and interferes with the chemical processes of the brain… LSD is a universally terrifying drug and I am alarmed by its spread into Vancouver high schools. Fifty pounds of it is enough to produce mental illness in everybody in North America. This is how powerful it is.”

McGeer was reacting to police reports that high school students were dropping LSD, and went on to describe how LSD use can lead to suicide, homicide, mental breakdown, and an addiction that is “every bit as hellish as heroin addiction.”

University officials were quick to respond to McGeer’s claims. UBC president Dr John B. Macdonald’s generous interpretation was that McGeer was speaking hypothetically, but that “no one at UBC had advocated the use of LSD.” The head of the faculty association said that McGeer’s statements were “a little bit half cocked” by implying local professors were actually promoting LSD use. The only professor that was identified as a promoter of LSD use was Timothy Leary, the Harvard psychologist who was famously fired years earlier for his work with hallucinogens. Curiously absent from the debate was anyone with any actual expertise regarding LSD.

Pat McGeer was at the forefront of a full-blown moral panic that resulted in his government outlawing LSD in 1967. McGeer claimed that the new law had eliminated the problem, at least amongst high school students. “I really believe that the popularization of LSD has passed its peak and that a much more common sense attitude is going to prevail,” he said. “This attitude is just a recognition that this is a dangerous agent.”

Although Hollywood Hospital plodded along until its demise in 1975, the drug panic pretty much killed serious research into LSD by the end of the sixties. Sandoz Pharmaceuticals stopped production and distribution entirely in 1965, claiming that widespread abuse of the drug, along with the inability to control its production and regulation and the unmanageable “flood of requests for LSD” it received combined to make it no longer worthwhile for the company despite “the important role that this substance could play as an investigational tool in neurological research and in psychiatry.”

Rear view of Hollywood Hospital, 525 Sixth Street in New Westminster, shortly before it shut down in 1975. This private facility was one of the main LSD research centres in North America. Celebrities, politicians, and anyone with $600 could come here for LSD therapy to treat alcoholism or anxiety and other disorders. Province, 8 July 1975

Al Hubbard, meanwhile, left Hollywood Hospital because he disagreed with Dr MacLean using LSD primarily as a money maker. Hubbard felt all along that it was a spiritual and therapeutic tool rather than a commodity and therefore that it should be freely distributed to the right people. The divergent views of the two men manifested in their pocketbooks: Hubbard had pretty much blown through his fortune and ended up having to sell his island sanctuary. MacLean became rich enough from Hollywood Hospital to purchase Casa Mia, the lavish mansion built by George Reifel, Hubbard’s old boss in the rum running business in the 1920s.

LSD’s reputation took its first hit with sensational media stories in the early 1950s that conflated its effects with mental illness. One of the first of these was “My 12 Hours as a Madman” in which reporter Sidney Katz tested “an experimental drug and explore[d] the terrifying world of insanity” for the cover story of the 1 October 1953 issue of Maclean’s Magazine. And of course Timothy Leary of “tune in, turn on, and drop out” fame helped strip away any aura of respectability or scientific legitimacy that LSD might once have had. For this, Hubbard literally wanted to murder Leary.

Revelations in the 1970s about evil mind control experiments that the CIA conducted at McGill University and elsewhere didn’t help the future of LSD research either. (Socred minister Rafe Mair looked for similar connections at Hollywood Hospital in 1980, but found no direct evidence of covert CIA or government LSD experimentation.) Only in recent years are researchers again looking at LSD and other psychedelic drugs for their potential therapeutic benefits. The snag this time around appears to be lack of support from governments still firmly entrenched in drug war thinking and pharmaceutical companies that prefer developing more profitable drug treatments that require more than a few doses.

Al Hubbard spent his final years living in a trailer park in Arizona and working as a security guard. He died 31 August 1982 at the age of 81.