34 Market Alley. This alley was once a commercial strip named after the market that operated on the ground floor of the original City Hall, just south of the Carnegie Library, and where the Asiatic Exclusion League had their rally before rampaging through Chinatown and Japantown in September 1907. The owner of an opium factory at 34 Market Alley received $600 compensation from the federal government for lost business in the days following the riot, which inspired Mackenzie King to draft Canada’s first drug prohibition legislation.

Situated in one of the grubbier Downtown Eastside alleyways, 34 Market Alley is a popular stop on local historical walking tours, and for good reason. An opium factory that operated here in 1907 inspired Canada’s first drug laws.

After the September 1907 rampage of the Asiatic Exclusion League through Chinatown and Japantown, the federal government appointed Deputy Minister of Labour and future Prime Minister William Lyon Mackenzie King to head a commission to investigate losses sustained during the rioting. Two of the largest claims of $600 each came from opium manufacturers. One was submitted by King Fung Co. at 517 Carrall Street, now the parking lot for Jack Chow Insurance. The other claim was for 37 Dupont Street (now East Pender), where Lee Yuen operated an opium factory, probably in the building on the rear of the lot designated 34 Market Alley.

Because Canada was trying to cultivate good diplomatic relations with Japan, King dealt with Japanese claims first, in October, the month following the riots. He rented Pender Hall at the corner of Howe and Pender for $5 a day and placed a notice in the News-Advertiser and World newspapers (but not the Province because it supported the Conservative Party and he was a Liberal) announcing that he would be taking submissions for damage claims.

Windows broken at 201 Powell Street in Japantown during the 1907 Asiatic Exclusion League Riots. Although there was significantly more damage done in Chinatown, Japanese claims for government compensation came much quicker because Canada was trying to build diplomatic relations with Japan. Japan’s victory over a European power – Russia – in 1905, led other European states and Canada to treat it as a serious player on the international stage, unlike China or the rest of Asia. Photo: Library and Archives Canada #C023555

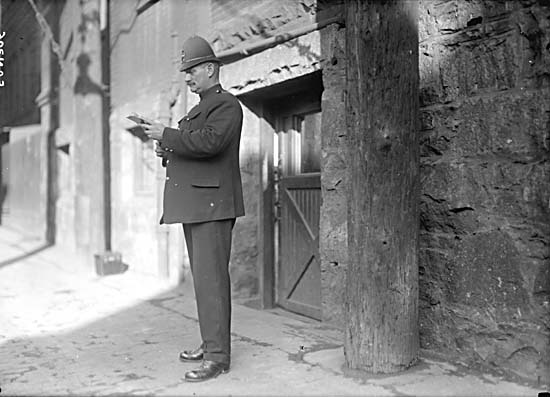

Besides claims for damages, King heard numerous opinions during his time in Vancouver. Chief Constable Chamberlin explained that the Japanese “had endeavoured to exaggerate the disturbance … they had a complete organization, and were prepared to shoot down whites if attacked; that he had to give orders through the police to have the Japanese pickets dispersed. They were standing at the corners with buglers, etc.” But though Chief Chamberlin apparently had sufficient men to disperse the Japanese, he told King that he was too short on manpower to handle the white rioters: “He thought the police force of the city inadequate for its size, and said that for a time, on the night of the 7th [September 1907] was unable to handle the situation, but subsequently got matters in hand,” King wrote in his diary, and observed that Chamberlin “seemed to share the anti-Japanese feeling.” Nevertheless, the Vancouver police did perform better in 1907 than during anti-Chinese riots in 1887, when they “strangely and persistently refrained from enforcing the law” and the provincial government had to send over special constables from Victoria to police Vancouver.

King wrapped up the Japanese portion of his Commission and approved a little more than $9,000 in compensation. It hadn’t yet been decided to give the same treatment to the Chinese, so King left the city. “Personally,” he wrote in his diary, “I would be much better satisfied with having only the Japanese claims to deal with.” But putting his own feelings (or laziness) aside, King believed that unless all claims were dealt with, “at some future time the matter will do harm to the Dominion.”

The Acland-Hood Hall, popularly called Pender Hall, at 804 Pender Street was where Mackenzie King conducted his investigation into compensation claims stemming from the 1907 anti-Asian riot. Less than two weeks earlier, Rudyard Kipling addressed the Canadian Club here. In 1910, Emily Carr exhibited her paintings at the hall, and the Vancouver Symphony Orchestra played its first gigs here in 1915. Photo by L. Frank, 1947, City of Vancouver Archives Bu N209

Mackenzie King finally returned to Vancouver in late May the following year to deal with Chinese claims and went through the same process. Compensation paid out to Chinese claimants was around $27,000. King rejected compensation claims for firearms, ammunition, and fire protection equipment that were purchased in case there were more attacks because he believed they were unnecessary safeguards.

Because much of the groundwork had already been done in the first inquiry, King had some extra time to delve a little deeper into the opium issue when it arose.

With Anti-Opium Leaguers as his tour guides, King visited the Carrall Street and Market Alley factories and found they were doing a booming business. One had been operating for ten years, employed ten people, and grossed $180,000 in 1907 alone, with a net profit of $20,000. The other operator had been at it for 21 years, employed 19 people, and grossed between $170,000 and $180,000 in 1907, netting a cool $15,000 for the year.

King learned that there was another opium factory in New Westminster and three or four more in Victoria. But the real shocker was that taxpayer money — in the form of compensation for lost business — would be going towards the production of opium, which was being “sold to white people as well as to Chinese and other Orientals” across the country.

William Lyon Mackenzie King was Deputy Minister of Labour in 1907 when he was appointed Commissioner to investigate compensation claims stemming from the Asiatic Exclusion League riots in Vancouver.

Opium had been a non-issue on the Canadian political landscape until Mackenzie King used his report on compensation to raise the hue and cry:

Regarding it as an anomaly that the Government of Canada should, under any circumstances, be held bound to make good pecuniary losses in an industry so inimical to our national welfare, and having regard to the discretion given me by my commission, I feel it my duty respectfully to submit that the operations of the opium industry in Canada should receive the immediate attention of the parliament of the Dominion, and of the several legislatures, with a view to the enactment of such measures as will render impossible, save in so far as may be necessary for medicinal purposes, the continuance of such an industry within the confines of the Dominion, and as will assist in the eradication of an evil which is not only a source of human degradation but a destructive factor in national life. This industry, I believe, has taken root and has developed in an insidious manner without the knowledge of the people of this country. Its baneful influences are too well known to require comment. The present would seem an opportune time for the government of Canada and the governments of the provinces to co-operate with the governments of Great Britain and China in a united effort to free the people from an evil so injurious to their progress and well-being. Any legislation which may be directed to this end, will have the hearty endorsement of a large proportion of the Chinese residents of this country, who, as members of an Anti-Opium League, are doing all in their power to enlighten their fellow citizens on the terrible consequences of the opium habit, and to suppress, as effectually as possible, the traffic which, for so many years, has been carried on with impunity.

King followed up that report with another specifically calling for anti-opium laws, in which he elaborated on the concern that opium use was not limited to Chinese users, a fact he felt would “appal the ordinary citizen.”

“The Chinese with whom I conversed on the subject,” King wrote,

assured me that almost as much opium was sold to white people as to Chinese, and that the habit of opium smoking was making headway, not only among white men and boys, but also among women and girls. I saw evidences of the truth of these statements in my round of visits through some of the opium dens of Vancouver.

The opium factory in Market Alley may have awakened Mackenzie King to the extent of the opium industry in Canada, but the real impetus for the war on drugs had more to do with international trade and politics than moral indignation or local concerns. China’s efforts to curb the opium trade began as early as 1729, but Britain, in its ambition to force China to open up to international trade, quashed those efforts by way of the Opium Wars of the mid-nineteenth century. The United States became interested in the suppression of opium later in the century, in part because it inherited its own opium problem when it took over the Philippines in the Spanish-American War.

More significantly, the US was eager to tap into Chinese markets, partly for economic gain and partly because it would allow them to compete head-to-head with their imperial rival, Britain, in the Chinese marketplace. The Americans had been shut-out of trade relations with China in retaliation for the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the brutal treatment Chinese émigrés were subjected to in the United States. President Roosevelt was advised that “the best way of re-establishing trade relations would be to show the Chinese government that America was sympathetic to the addiction problem and wanted to help resolve it.” The result was a series of international anti-opium conferences beginning in 1909 in Shanghai.

Whatever Mackenzie King’s personal feelings about drug addiction or white girls being corrupted by Chinese traffickers, he was above all a savvy politician who saw in his investigation into the Vancouver riots an opportunity to ingratiate himself and Canada with the nascent international war on drugs. King’s efforts resulted in the first significant drug prohibition laws in Canadian history, which were enacted in time for the 1909 Shanghai conference. This and subsequent conferences in turn fuelled further expansions of Canada’s drug laws.

Market Alley [pdf] took its name from the market that operated on the ground floor of the original City Hall, just south of the Carnegie Library. The sign marking 34 Market Alley is the only visible reminder of the bustling commercial strip that existed here a century ago. That said, the drug trade that Mackenzie King characterized as “an evil which is not only a source of human degradation but a destructive factor in national life” is flourishing as never before in this and nearby alleys and streets, despite the unprecedented amounts of money and resources the government now spends trying to suppress it.