Patricia Hotel, 1917, the year prohibition and hot jazz came in. Photo by Stuart Thomson (cropped), City of Vancouver Archives #99-187.

[Note: This post contains material I’ve covered elsewhere along with new research in an attempt to assemble the most comprehensive account of Vancouver’s early jazz scene to date].

Shortly after alcohol prohibition came into effect in October 1917, a lively hot jazz scene sprouted in Vancouver. Hotel bars at the Patricia, Irving, and the Bodega began featuring live music to make up for the loss of booze sales, and by 1919, the Patricia Cabaret was the hottest jazz club on the West Coast, thanks to its house band featuring Oscar Holden, Jelly Roll Morton, Albert Paddio, William Hoy, Lillian Rose, Leo Bailey, and Ada “Bricktop” Smith.

Curiously, jazz only became a pop culture sensation after the March 1917 release of the very first jazz record, Livery Stable Blues by the Original Dixieland Jass Band, mere months before the Patricia debuted its jazz cabaret. Vancouver had already been exposed to jazz when the Original Creole Orchestra played the Pantages in 1914 and 1916, but that hardly seems sufficient to set the stage for a local jazz scene to emerge. So how did Vancouver—geographically and culturally miles away from the jazz centres of New Orleans and Chicago—become a hotspot for the new music in the Pacific Northwest so early in its history? What little evidence that exists suggests sportsman George Paris had a lot to do with it.

George Paris was an important figure in Vancouver’s sports community a century ago. Born in Truro, Nova Scotia, he came to the Pacific Northwest in the early 1900s after a stint in Montreal training its police force how to fight. He was BC’s first heavyweight boxing champion, an accomplished sprinter, lacrosse player, and clog dancer, but local jocks knew him best as a coach, referee, and an athletic trainer of the Vancouver police, the Seattle Giants baseball team, the Vancouver Lacrosse Club, and boxing legend Jack Johnson, among others. Johnson’s first stop after becoming the first black heavy weight boxing champion was Vancouver, and George Paris hosted him at his home and in an exhibition bout at the Vancouver Athletic Club in 1909.

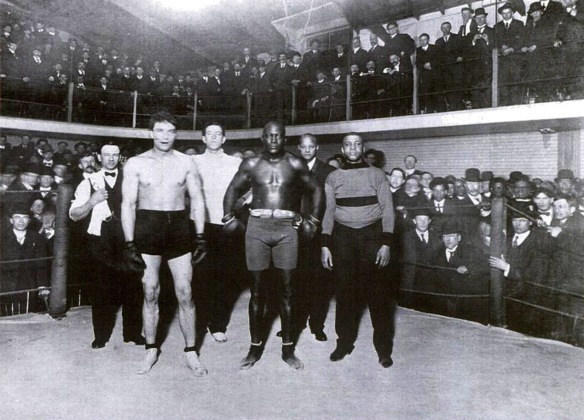

Victor McLaglen, Jack Johnson, and George Paris at the Vancouver Athletic Club, 1909. Paris put up Johnson and his white girlfriend at his house because most Vancouver hotels wouldn’t take in a mixed-race couple. Paris maintained a relationship with Johnson that included travelling to Europe as his personal trainer in 1914, and may have been introduced to the early jazz scene through Johnson. Image courtesy Heritage House.

At some point Paris also took up drumming, and was recruited to put together a jazz band for the Patricia Café. When the cabaret opened on 7 October 1917, Paris’s band was followed by the Empress Jazz Orchestra, from the theatre a block to the west of the Patricia. Nothing else is known about the Empress band, except that it appears they were the first local group to advertise themselves as a jazz band, after “jass” had become “the craze in all the large eastern cities.” Without recordings or contemporary descriptions of their music however, there’s no way to tell if their music was authentic “hot” jazz rather than its precursor, ragtime.

The Empress Jazz Orchestra, from the Empress Theatre on East Hastings at Gore Avenue, opened the Patricia Cabaret at the onset of prohibition. Photo by Zubick, 1 November 1919, City of Vancouver Archives #19-81

An avid sports fan himself, George Paris made annual pilgrimages to the World Series, which in those days often meant travelling to Chicago. In 1910, he brought a young Chicagoan named Helen Smith to Vancouver to become his bride. A gap in the city directories suggests that the couple may have spent much of 1911 and 1912 in her hometown. This is likely when and where Paris was introduced to jazz music.

Chicago was going through a demographic shift in 1912, as Southern blacks were flooding into the city during the “Great Migration.” The mass movement of blacks also served as a conduit for the dissemination of jazz music, and Chicago was well on its way to becoming the second city of jazz after New Orleans. For four months at the end of 1912, George Paris’s friend, Jack Johnson, ran the hottest club in town.

Jack Johnson’s Café de Champion, 41 West 31st Street, Chicago, 1912. Screen grab from Unforgivable Blackness, Ken Burns Jack Johnson documentary.

Johnson opened his Café de Champion in Chicago’s “Black Belt,” the city’s South Side African American district, in July 1912. Inspired by cafés he visited in Europe, it was lavishly outfitted, featuring paintings valued at $15,000 and solid silver water pitchers and monogrammed silver spittoons. Café de Champ was a black and tan cabaret, or in Johnson’s words, catered to the “African aristocracy” and “vanquished but aspiring” whites. It also featured live music by “the best colored talent in the country,” and Johnson was known to sit in with the band with his double bass, which perhaps inspired Paris to try his hand at drumming.

“Saturday Night” by Archibald J Motley Jr (1935). Although painted years later, this image depicts Jack Johnson’s black and tan Cafe de Champion, one of the top clubs in Chicago during its brief existence in 1912. Motley is best known as a Harlem Renaissance painter but in 1912 was studying art in Chicago. Bricktop was a popular entertainer (and possibly the dancer depicted here) at the Cafe de Champion, which was likely frequented by several others who would later be affiliated with Vancouver’s Patricia Cabaret. Painting from the collection of the Howard University Gallery of Art.

White America was openly hostile to Jack Johnson and his café. A campaign to find a “Great White Hope” who could retake the heavyweight title failed, so Johnson was instead charged under “white slavery” laws for crossing state lines with a white woman. Johnson’s café license was revoked four months after it opened and the pugilist went into exile in Europe. (He was back in the States in the 1920s and tried his hand in the cabaret business one last time with the Café de Luxe in Harlem, but his gangster investors took it over and renamed it the Cotton Club).

Despite its brief lifespan, Café de Champion influenced the emerging cabaret scene on Chicago’s South Side in terms of a racially integrated clientele and showcasing the music that would eventually be called jazz. But it wasn’t the first of its kind. One of Johnson’s favourite Chicago hangouts and a likely inspiration for his own café was the Marquette, a cabaret run by Bill Bowman, future manager of Vancouver’s Patricia Cabaret. The Marquette began as a private club for black men, but at the end of 1911, Bowman was converting it into a “full-blown cabaret.”

Oscar Holden, the leader of the Patricia Jazz Orchestra from 1919 to 1921. Originally from Tennessee, Holden played with some of the top early jazz players in the American South and Chicago, and finally settled in Seattle, where he helped pioneer the jazz scene around Jackson Street in the 1920s. (Screen grab from “Community Stories: Jackson Street“)

Other future members of the Patricia house band were in Chicago in 1912 as well. Jelly Roll Morton later said that’s when and where he first saw Oscar Holden play piano, seven years before Jelly Roll played in Holden’s big band in Vancouver. Morton also said he had known Bricktop Smith since she was “just a kid.” In 1912, she was a precocious eighteen year-old singing at Café de Champion, and in the video below, says Morton was her piano player there. George Paris most likely recruited Bill Bowman to take over management of the Patricia Cabaret, and Bowman in turn was likely the one who brought in Oscar Holden as band leader and clarinetist, Jelly Roll on piano, and Bricktop as a singer. One source says that Bowman persuaded Jelly Roll to come to Vancouver just after Morton lost his shirt in a card game in Tacoma. Morton only lasted a couple of months at the Patricia and Holden took over piano duties.

Bricktop Smith on Italian television in 1970. After the scene fizzled in Vancouver, Bricktop made her way to Europe where she, with the help of Cole Porter, opened “Chez Bricktop,” Europe’s most renowned jazz-age cabaret.

George Paris left the Patricia when the Chicago crew took over, but joined up with a railway porter named Elmer “Pee Wee” Malone in a big band at the Hole in the Wall club at 1164 Richards Street. Paris listed his occupation as “musician” in the 1920—1922 city directories and then resumed his more reliable career as an athletic trainer.

**********

The first time jazz was performed in Vancouver was in 1914 at the Pantages Theatre. The Original Creole Orchestra (or “Band”) was led by Jelly Roll Morton’s brother-in-law, Bill Johnson, and featured legendary trumpet player Freddie Keppard. They were from New Orleans and their 1914 tour of the Pantages vaudeville circuit has been credited for spreading authentic hot jazz music outside of Dixie. Years earlier, the Creole Band toured west from New Orleans to California, and in 1908 were temporarily based in Oakland. On June 21st of that year, they performed at a baseball game and clearly made an impression on a reporter from the Oakland Tribune:

For the edification of the assembled “Bugs” and “Bugines,” Mr. W. M. Johnson’s world-renowned Creole Orchestra shattered the air with melody and enlivened the proceedings. Mr Johnson’s Creoles put on tap a brand of rag time music that thrilled the bunch to their toes, and the chivalry and beauts cheered the musicianeers to the echo after each piece.

Mr. Johnson’s got some band, bo. ‘Taint organized none like dose raiglar regimental bands; nor does it worry itself by carrying music rolls. That orchestra includes and contains one snare drummer, greatest ever; one trombone player, unrivalled; a cornet player, unmatched; a mandolin and guitar twanger and a bass viol., the latter three of which dispenses sounds dat shualey can set some feet to movin’ …

Mr. Johnson and his Creoles are shualy an obligin’ lot, for they toots a heep after dey starts ‘er up, and keep a-tootin’ and a blowin’ and scrapin’ until the last fan ambles out of the park.

The rag that orchestra dispensed, free gratis to the fan, was of a new and weavy pattern. The gent with the trombone just cut holes in dat ole atmosphere, and when he got off to a runnin’ staht in any one piece he always finished head up and tail out ahead of his companion pieces in the picture. The cornet boy also trifled some with his instrument, and when he put de gumbo stuff on dat New Orleans rag dey was some shakin of feet dat resembled yards of fire hose in the left field bleachers. The mandolin and guitar boys were dere wid dat shivery stuff, and when dey tinkled they shualy played music till de cows come home. The man wid de voil [double bass] cut up some stuff dat was sharp as a razah and keen as a yen hok.

“New and weavy pattern” suggests a departure from ragtime music and “nor does it worry itself by carrying music rolls” hints that band members were improvising. Keppard putting “de gumbo stuff on dat New Orleans rag” with his cornet could be referring to a soulful or bluesy sound not associated with ragtime. In other words, the Tribune is describing music with all the defining characteristics of a modern “hot” jazz band, way back in 1908.

Bill Johnson, Freddie Keppard, and the Creole Band eventually returned to New Orleans, where they added “Original” to their name to distinguish themselves from Creole Band imitators. Albert Paddio, the “unrivalled” trombonist who “cut holes in dat atmosphere,” decided to stay on the Coast, in California and Seattle, perhaps due to legal and personal problems he had in Louisiana. So although he wasn’t in the Creole Band when they first introduced Vancouver to jazz, Paddio did play in the Patricia house band in 1919.

Salty Dog Blues by Freddie Keppard’s Jazz Cardinals (1926). Keppard is one of the most celebrated early jazz players. He played Vancouver’s Pantages Theatre twice with the Original Creole Orchestra in 1914 and 1916. Patricia Cabaret trombonist Albert Paddio played with Keppard in the original lineup of the Creole Orchestra. Jelly Roll’s brother in-law, Bill Johnson played bass and banjo, and was the band’s leader.

The only known review of the Patricia Cabaret band was penned by a night watchman visiting Vancouver from Langley in October 1920. He doesn’t name the band or venue, but he’s almost certainly describing Oscar Holden on piano and Albert Paddio on the trombone:

A colored orchestra was busy making the welkin ring. The dark curls and features of the pianist, outlined against the white sheet of music, made a really striking contrast. Indeed, I thought it was an ideal study in black and white—and, O Boy! You should have heard the notes come pattering from that music box just like hailstones falling on a corrugated roof. The trombone player also took my fancy, with his alternate puffing at a big black cigar and blowing out his jazz-notes.

Fellow musician Reb Spikes described Paddio as “one great trombone player,” and Jelly Roll Morton said that Paddio “never got East so none of the critics ever heard him, but that boy, if he heard a tune, would just start making all kind of snakes around it nobody ever heard before.” No one knows for sure what happened to Paddio, but one contemporary thought he lost his mind and another vaguely remembered hearing that he died in Vancouver. The evidence cited above is the only known documentation of his contribution to jazz, but it sounds like he could have been a major character in jazz history instead of an obscure footnote had circumstances been more favourable.

Jelly Roll Morton is the best known of the Patricia musicians, which unfortunately has overshadowed other important members such as Holden and Paddio. Part of the reason is that Morton claims in his autobiography (as told to Alan Lomax) that he was the bandleader when in fact Holden held that position for about two years while Morton was only in the band for about two months. It’s likely that Morton was fired by either Holden or Bill Bowman, given his reputation for being difficult to work with. There was also bad blood between him and Bricktop that predated and perhaps cut Jelly Roll’s time at the Patricia short.

Ferd “Jelly Roll” Morton and Ada “Bricktop” Smith, Los Angeles, 1917, before (according to Morton) she had him replaced because he caught her stealing. The consequent bad blood between them could explain why Jelly Roll didn’t last long at the Patricia in 1919. (Frank Driggs Collection)

In his version, Morton spotted Bricktop stealing money when they were performing together at the Cadillac Club in Los Angeles. He called her on it, and so, he says, she had him replaced with another piano player. “It is quite likely that the gig at the Patricia became the sequel to the one at the Cadillac,” writes one historian, “and with the same result: Bricktop in, Jelly out.” Bricktop felt no need to respond to the allegation in her own autobiography.

Bricktop’s final performance, a cameo in Woody Allen’s 1983 mockumentary, Zelig.

Jelly Roll Morton came back to Vancouver in the spring of 1921 and put together a trio to be the house band of the Hotel Irving on the northeast corner of Hastings and Columbia. He brought up Doc Hutchinson from Baltimore to play drums and Horace Eubanks from East St Louis on clarinet; Eubanks played on Morton’s first recording sessions a couple of years later.

Someday Sweetheart by Jelly Roll Morton’s Jazz Band. This is from Morton’s first recording sessions in October 1923, and included Horace Eubanks, his clarinetist from the Hotel Irving in Vancouver two years earlier. Music from these sessions are probably the closest we can get to sampling the sounds of Vancouver’s prohibition-era jazz scene.

Morton told Alan Lomax that his band played at the Regent, but also spoke of his boss, Paddy Sullivan, being a “big time gambler.” Paddy Sullivan ran the bar for his brother, John L Sullivan, the owner of Hotel Irving, which is on the same block as the Regent and would therefore be easy to confuse years later.

Jelly Roll’s longtime girlfriend, Anita Gonzales, described singing at the Irving one night, and Morton’s insane jealousy:

One night, playing for Patty Sullivan’s Club in Vancouver, the girl singer got sick and, before Jelly could stop me, I went up and started singing and dancing. Right there Jelly quit playing and, because he was the leader, the rest of the band stopped playing, too, but I kept straight on with my song. When I was finished, there was stacks of money on the floor. Jelly was furious. He dragged me outside and made me swear never to sing or dance again, but don’t think he hit me. Jelly was a perfect gentleman.

Jelly Roll only lasted two or three months at the Irving before leaving Vancouver for good.

Another noteworthy jazz-age venue was the Lodge Café, which opened in May 1919 at 556 Seymour Street. According to the Chicago Defender, the house band in December 1920 included saxophonist Frank Waldron, trombonist Baron Morehead, Olive Bell, Adolph Edwards, James Porter, Lillian Goode, Bettie and Clifford Ritchie, and Esmerelda Stathem. Morehead went on to play trombone with Fats Waller, and the Defender noted that Stathem had been “one of the Stroll’s most popular entertainers,” referring to Chicago’s cabaret strip on State Street.

Frank Waldron, ca. 1925 when he was playing trumpet with the Wang Doodle Orchestra in Seattle. Photo courtesy Black Heritage Society of Washington State ##2001.14.2.16E (cropped)

Much of Vancouver’s jazz scene migrated to Seattle after prohibition was lifted in BC in 1921. Oscar Holden has been called the patriarch of Seattle’s jazz scene that flourished on Jackson Street (after Vancouver’s scene withered), and left a slew of musical descendants. By all accounts he was a phenomenal musician, classically trained, and with a muscular “stride” piano style in the vein of Fats Waller or even Art Tatum. He fled Tennessee to escape the Jim Crow racism he experienced there, played on Mississippi riverboats with the likes of Louis Armstrong and honed his musical style in Chicago before coming to the Pacific Northwest. Had he recorded or travelled instead of settling down and raising a family, Holden might also be a better known jazz pioneer today outside of the Pacific Northwest.

Bill Bowman managed cabarets in Seattle in the 1920s and Frank Waldron, the saxophonist at the Lodge Café, became Seattle’s premier jazz teacher, counting among his students Quincy Jones and Buddy Catlett, one-time bass player for Louis Armstrong and Count Basie. He’s another one who never recorded, but music that Waldron published in 1924 is being commemorated with recordings by Greg Ruby and the Rhythm Runners, a prohibition-era jazz band. The first three tracks were released last year.

Low Down, written by Frank Waldron and performed by Greg Ruby and the Rhythm Runners from the album Washington Hall Stomp.

All I Need, written by Oscar Holden and performed by his daughter Grace. Like many important early jazz artists, Oscar Holden never recorded.

The inevitable underground scene created by prohibition was important in the development of early jazz, and the stricter and much longer prohibition in the States no doubt made Seattle a more fertile stomping ground for jazz. Seattle’s black population grew substantially during the Great Migration as well, likely giving it a larger and more receptive audiences for the new music than Vancouver. In contrast, Jelly Roll Morton claimed that the crowd at the Patricia “didn’t understand American-style cabarets,” and Bricktop Smith’s description of a brawl there on New Year’s Eve in 1920 makes it sound like whiskey and fighting were the main attraction, not the music:

Bowman’s biggest customers—and I do mean big—were the Swedish lumberjacks who came into Vancouver on their time off. Tall, strapping fellows, they could make a bottle of whiskey disappear in no time. Pretty soon they’d be drunk and ready to fight. I wanted no part of these fights and would make myself scarce when one broke out—except on New Year’s Eve of 1920 in the fight to end all fights.

No one knows what that fight was all about. Everybody was beating up on everybody else. Bowman’s was a large place, and “everybody” means about three hundred people. I remember all the fists flying and glass breaking, but that’s all I remember. It was one of those “special occasions” when I lost count of how many drinks I’d had.

The next thing I knew, I was in a bed in a white room. My right leg was in a splint, and my head felt as if it were about to come off. I was in a hospital, and my leg was broken.

A gal I knew called Dago was standing by the side of my bed. I couldn’t believe it when she told me I’d kept trying to get into the brawl the night before. “You kept running into the middle of all those punches and someone kept pushing you back out, but that didn’t stop you. You got right back in the middle of it again, and got pushed out again. But this time you fell down a flight of stairs.”

Ada “Bricktop” Smith in Vancouver, 1920. At the time, she was singing in the Patricia Orchestra and living on East Georgia Street in today’s Strathcona. Later she became best known for running her own popular cabarets in Europe. From Bricktop by Bricktop with James Haskins (Atheneum, 1983).

Vancouver’s musicians’ union also made it difficult for Americans coming to play on this side of the line, which also would’ve made Seattle more attractive for jazz artists. Jelly Roll complained about the union making it difficult to get across the border, even after he threatened to get all the Canadian musicians thrown out of the US. At the end of the twenties, the union began a complete boycott of American acts that was in place for eleven years, until Duke Ellington ended the drought in 1940.

For more on early jazz in Canada, see Such Melodious Racket: The Lost History of Jazz in Canada, 1914-1949 by Mark Miller, who first uncovered this history.

For Seattle’s jazz history, see Jackson Street After Hours: The Roots of Jazz in Seattle by Paul de Barros. On the Original Creole Orchestra, see Pioneers of Jazz: The Story of the Creole Band by Lawrence Gushee, and for an in depth account of Jelly Roll Morton’s time on the coast, see Dead Man Blues: Jelly Roll Morton Way Out West by Phil Pastras.

![Lee Jones, an American "sporting girl" arrested as a "keeper of a disorderly house" for turning tricks in her room above the Utopian Club, a brothel at 169 Harris [Shore] Street on 22 July 1913. City of Vancouver Archives, VPD series #S202, Loc. 37-C-9](https://pasttensevancouver.files.wordpress.com/2014/12/sporting-girl-169-harris-1913.jpg?w=404&h=269)