Guy Glover and other cast members of Waiting for Lefty at the Dominion Drama Festival in 1936. After the war, Glover joined his partner, Norman McLaren, producing films at the National Film Board of Canada. This photo was taken by legendary Canadian photographer Yousuf Karsh early in his career. Library and Archives Canada, Yousuf Karsh Fonds, e010752218

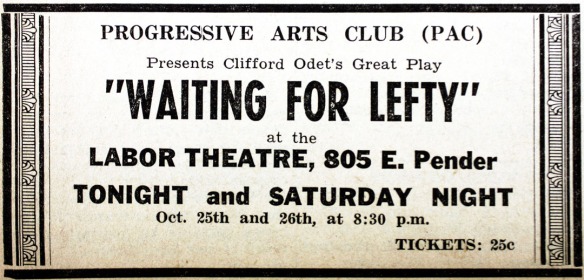

Seventy-five years ago, a surprise runaway hit was turning Vancouver’s amateur theatre scene on its head. The Progressive Arts Club’s production of Waiting for Lefty played to packed houses around the Lower Mainland and each performance ended with a standing ovation and exuberant applause. The play toured across the country in 1936, culminating in a performance in Ottawa at the Dominion Drama Festival, a prestigious national amateur theatre competition. Waiting for Lefty was BC’s entry in the festival and took home the prize for the best English language play that year.

What made the success of Waiting for Lefty remarkable is that many of the cast and crew were unemployed and/or had no previous theatre experience. It was also Vancouver’s introduction to the workers’ theatre movement that was sweeping North America and Britain.

The Progressive Arts Club of Vancouver was started by civil rights lawyer Garfield King along with Guy Glover, whom he worked with at Vancouver Little Theatre. King was frustrated with the “namby pamby” and socially irrelevant plays being produced by the Little Theatre and approached Glover about starting a workers’ theatre troupe composed mainly of unemployed Vancouverites. They each put $10 into the project and arranged to use the Ukrainian Labour Temple for workshops and rehearsals.

The Ukrainian Cultural Centre (formerly the Ukrainian Labor Temple), 805 East Pender Street in Vancouver's East End. The Progressive Arts Club recruited cast & crew, rehearsed, and performed Waiting for Lefty here in 1935.

There was already a Progressive Arts Club in Toronto that in 1933 produced a controversial play called Eight Men Speak that depicted the persecution and imprisonment of Communist Party leaders under the notoriously anti-democratic Section 98 of the Criminal Code and the attempted assassination of party leader Tim Buck during his incarceration at Kingston. Eight Men Speak was only performed once before the Toronto Police Department’s Red Squad shut it down. The play was part of a major campaign to have Section 98 repealed, which came on the heels of a massive petition of 459,000 signatures collected by the Canadian Labour Defense League (CLDL) that failed to impress Prime Minister RB Bennett.

Garfield King was one of the key lawyers working for the Canadian Labour Defense League, and as such would have been up to speed on developments elsewhere, such as the production and suppression of Eight Men Speak in Toronto. King obtained the script and rights to perform Clifford Odets’ Waiting for Lefty nine months after it premiered in New York, where it was an instant hit.

Garfield King was a prominent lawyer with the Canadian Labour Defense League and producer for Vancouver Little Theatre when he and Guy Glover formed the Progressive Arts Theatre in 1935. Before becoming a lawyer, King was employed as a photographer at Stanley Park's Hollow Tree.

The audience was wildly enthusiastic in their response to the play, which was loosely based on the 1934 taxi strike in New York. Never before had they witnessed a stage drama that resonated with their lived experiences and echoed the dramas that were playing out on the streets in 1935. Years later, one audience member fondly recalled that it was “as if your own life was being played out on the stage … it made your own problems seem more significant and understandable…[and] articulated those emotions which the injustices of the present day had laid in every heart.”

One aspect of workers’ theatre that contributed to the sense of realism was the use of techniques designed to break down the “fourth wall” separating performers and audience. Planting cast members in the audience was one way to accomplish this, but it could also create confusion. One of the actors, Harry Hoshowsky, recalled that at one of the early performances

there was almost a riot during the spy episode, when I was making statements to the executive on stage and Mike Kunka was going to contradict them. He was already making preposterous asides to the audience. The people were almost sure they were at a meeting. They tried to contain him … people moved right out of their seats and bodily tried to contain him … he was a little afraid that he wasn’t going to get up on the stage. We had others spotted around at later performances to ensure that he could get away.

Not everyone viewed the play in a positive light. Local poet and fascist pundit Tom MacInnes condemned the play in one of his radio broadcasts as “the red beast of Moscow.” An anonymous reviewer in a North Vancouver paper called it a “dramatic absurdity,” “foreign,” “crude,” “vulgar,” “indecent,” and “offensive.” In response, the Communist BC Workers’ News pointed out that the main bone of contention was that Waiting for Lefty was a working class story that this and other critics could only read as propaganda, not bona fide art

because the play revolved around workers instead of salaciously portraying the pornographic preludes to fornication in the bedroom farces and sexy bourgeois plays which are manufactured by hacks to satisfy the jaded senses of the exploiters of the people.

Indeed, the play triggered a public debate about whether propaganda and art were mutually exclusive, including a symposium following a performance of Lefty at the Empress Theatre. It appears defenders of the play won the argument with the contention that bourgeois drama could just as easily be read as propaganda since it promoted a middle-class worldview.

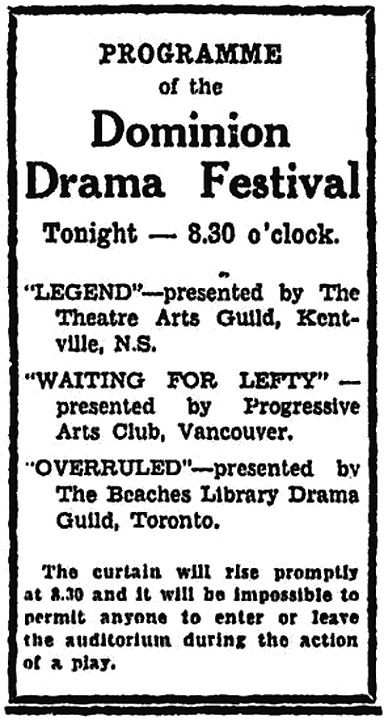

In the audience at one of the early performances of Waiting for Lefty was RCMP Superintendent Herbert Darling. He had recently begun a two-year stint with the Vancouver Police Department, having been seconded by the RCMP as part of the campaign to modernize the VPD and fight communism in the city. Darling arrived too late for the relief camp strike that culminated with the On-to-Ottawa Trek or the Battle of Ballantyne Pier (although the waterfront strike was still dragging on).

The quintessential police bureaucrat, Herb Darling was the Canadian state’s top expert on Communism and intelligence. In 1931 he co-authored the internal RCMP report that made the case that the Communist Party was in fact an illegal organization under the provisions of Section 98. The report provided the rationale for the arrest of the Party’s top leaders, the subject matter of Eight Men Speak.

Supt. Herbert Darling, Mountie and amateur theatre critic. Darling was loaned to the Vancouver Police Department for two years to build its intelligence capabilities and modernize its bureaucracy as part of the fight against the Red Menace. Needless to say, he wasn't impressed with Waiting for Lefty. Regina Leader-Post, 31 Aug 1945.

Darling attended one of the early performances of Lefty and wasn’t too impressed. He reported that it was a full house and that “judging from the looks of some of the people in the audience … I would say some of them were quite decent respectable men and women.” As for the play itself, it was

a Labor Propaganda revolutionary spreading drama and the actors are gathered from the local talent in the communistic element of Vancouver … In many parts of the play the language is worse than you would hear in any cheap sporting house, but at that the class of actors and actresses in the play seemed to get a thrill out of using it.

The Vancouver Police subsequently attempted the same tactic that the Toronto Police used to successfully shut down Eight Men Speak two years earlier. Chief Constable Foster wrote to the Attorney General that in view “of the filthy language used, the proprietors of the building where the play was produced have been advised that their license will be cancelled if it is shown again.” The A-G responded that

stage plays are not subject to censorship. Matters of this kind are covered by the relevant sections of the Criminal Code and I feel sure that should the information you have be placed before your prosecuting department, action could be taken against the players for the use of indecent and blasphemous language.

Instead, Chief Foster arranged a meeting between Garfield King and Supt. Darling to discuss Lefty. Darling told King that it was not his place to play the role of censor. He had seen the play and did not like it, but acknowledged that it presented “certain aspects of present social conditions and frankly admitted the right of the author to do this in an art form.” His main issue was the vulgar language used in the play. At one point in the meeting, Darling proposed that King give him a copy of the script and that he would point out the offending expressions. “Indeed this was his own suggestion,” according to King, “but when I pointed out that this procedure would immediately cast him in the role of censor, he agreed that the proposal was not wise.”

After his meeting with Darling, King wrote an open letter to Chief Foster explaining his position and the concessions he agreed to for the show to go on.

It appalls one to realize that in a metropolitan city like Vancouver, an inspector of rooming houses, palmists, restaurants, etc. is vested with the arbitrary powers of veto over a play, which, as his letter indicates, he has neither seen nor read,– in this case a play currently produced and acclaimed in New York and London … Even in England the function of literary and dramatic criticism, with power to censor, is entrusted to a specially trained and highly educated official entirely removed from police affiliations. The scales of judgment in these fields are too delicate for military and police hands.

King did agree to change two words in order to appease the authorities: “fruit” and “sonovabitch.” In the case of the former, King quoted its use in the script:

Labor Spy: The time ain’t ripe. Like a fruit don’t fall off the tree until it’s ripe.

Voice: Sit down, you fruit!

“I’m told that ‘fruit’ has a double meaning and carried an unpleasant connotation,” King wrote, “so we will drop the ‘fruit’ and substitute ‘lemon’ or possibly some vegetable.”

A third offending word King refused to change: “the good old English expression ‘goddam,’” claiming that according to the Oxford English Dictionary it was not blasphemous and could be traced back to Joan of Arc, who used it as a synonym for “Englishman.” Besides, “not only have I Shakespeare, George Bernard Shaw and a host of dramatists on my side, but I feel that in this crisis I can absolutely rely on the support of the entire uniformed section of the police force!”

Foster and Darling relented, and the show went on. Guy Glover later even credited Foster’s efforts with ensuring that Lefty continued, noting that Foster was also the vice-president of Vancouver Little Theatre. In contrast, a faculty committee at the University of British Columbia refused to grant permission for a student production of Waiting for Lefty, and the board of a Seattle theatre company pulled the plug after only one performance of Lefty in January 1936.

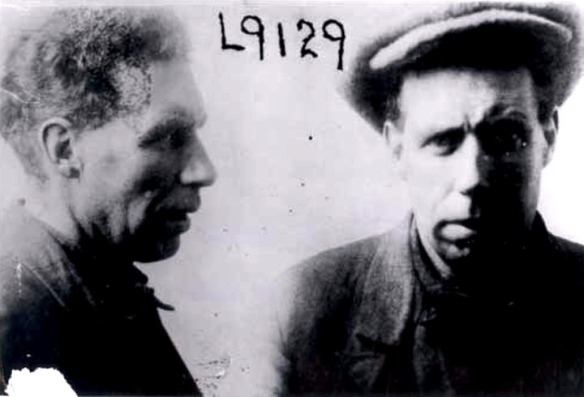

Mugshot of Stewart "Paddy" O'Neil, taken following his arrest in the Regina Riot. A Newfoundlander and First World War veteran, O'Neil headed the Workers' Ex-Servicemen's League in the 1930s and was part of the On-to-Ottawa Trek delegation that went ahead and met with Prime Minister RB Bennett in Ottawa in 1935. He returned to Vancouver after the Regina Riot and played a union member in Waiting for Lefty. Instead of returning to Ottawa to perform in the Dominion Drama Festival, O'Neil joined the Mackenzie-Papineau Battalion to fight fascists in the civil war in Spain, where he was killed. City of Regina Archives Photograph Collection, CORA-RPL-A-300

The BC Provincial Police also monitored the play, but was told by the Deputy Attorney General that the language issue was “more a matter of bad taste than a criminal offence.” He also pointed out that Lefty had been chosen to represent BC in the Dominion Drama Festival. Still not convinced, the BC Police claimed in a follow-up report that the play “was not a bona fide entry in the Annual Dramatic Competition. It was put on solely for the purpose of propaganda and run under the guise of a competing play simply because it would not otherwise have been tolerated by the authorities.”

While language was ostensibly the issue driving efforts to suppress Lefty, the popular assumption was that the real reason was its militant, pro-labour content. Many people suspected that the Citizens’ League, a fascist vigilante/propaganda outfit set up by the Shipping Federation to help crush the ongoing longshoremen’s strike, was pressuring the police behind the scenes to stop Lefty.

For its part, the RCMP mentioned Lefty in its Security Bulletins, intelligence summaries that were regularly sent to Ottawa. The report simply noted that Waiting for Lefty was a hit in Vancouver and cited a New York critic’s impression of the play when it showed in that city:

A Milestone was … the appearance of ‘Waiting For Lefty’, a fifty-minute play on the New York taxi strike … this drama, with its head-on union meetings scenes, its flashbacks into the homes of cab drivers, its action swirling from stage to orchestra pit, and back to stage again … the most directly agitational of all working-class plays written to date in America, it added stature to revolutionary drama.

Unemployed protesters marching past the Empress Theatre on Hastings at Gore, June 1938. Waiting for Lefty played at least twice here in 1936, first when it won the regional leg of the Dominion Drama Festival, and again as a fundraiser for the trip to Ottawa. After the latter performance a symposium was held to determine whether propaganda and art were mutually exclusive. Photo: VPL Special Collections, #1293

Waiting for Lefty wasn’t expected to be a serious contender in the contest to represent BC at the Dominion Drama Festival. Most people assumed it would come down to the Vancouver Little Theatre and the Strolling Players entries. Instead, the adjudicator, renowned British producer Allan Wade, awarded first place to Lefty, giving the performance and its fresh approach the highest praise:

[It was] the nearest approach to professional standard I have ever witnessed by a group of amateurs … [Waiting for Lefty] was one of several plays lately written that will help make the theatre what in its great day it always was – a forum, a communal institution and instrument in the hands of the people for fashioning a sound society.

Vancouver Little Theatre resented that “a cheap piece of stark realism” performed by “a neophyte group of mostly ethnic actors” was selected. Its president, Citizens’ League supporter and anti-union activist General Victor Odlum, excluded the Progressive Arts Club from his post-festival party.

To get to Ottawa, the Progressive Arts Club had to do some serious fundraising. They toured Lefty around the province, including performances at Oakalla Prison Farm, Victoria, and a midnight show at the prestigious Orpheum Theatre that was so popular that BC Electric Railway scheduled extra streetcars to allow theatre patrons to get home after the performance.

In light of the increasing popularity of the play and local pride for BC’s official entry at the Ottawa festival, even Vancouver Little Theatre came around and agreed to perform on a double-bill with Lefty to assist with fundraising. General Odlum even moderated the art-versus-propaganda symposium at the Empress Theatre.

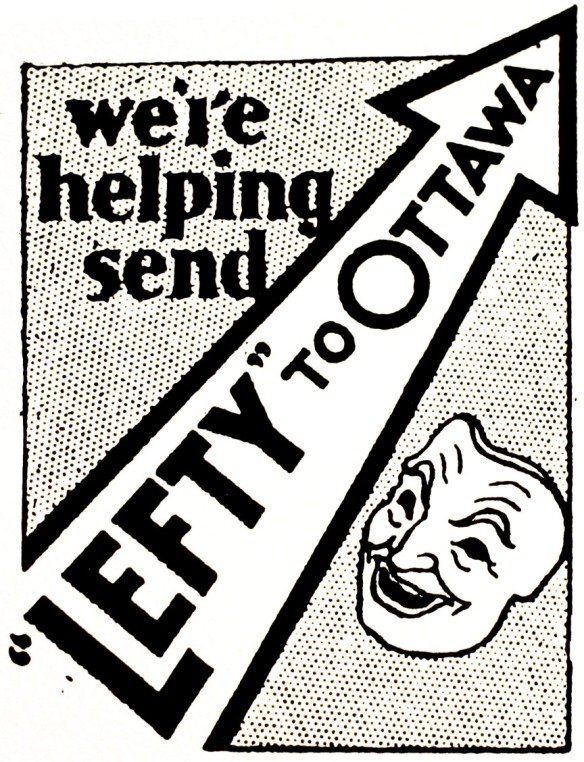

Flyer for the "Tag Days" held to raise funds to send the Progressive Arts Club to Ottawa to perform Waiting for Lefty as BCs entry in the 1936 Dominion Drama Festival. From Stage Left: Canadian Theatre in the Thirties by Toby Gordon Ryan (Toronto: CTR Publications, 1981).

The Progressive Arts Club also held a “tag day,” on the street solicitation of donations to help fund the trip east. Some passersby who hadn’t yet heard of the play saw the “We’re Helping Send Lefty to Ottawa!” banners and asked why “Lefty” doesn’t just ride the rods for free like everyone else.

With proceeds from the tag day and the earnings from 25 performances, the Progressive Arts Club took the train to Ottawa, stopping along the way to further fundraise by performing in various cities. Despite their lack of prior theatre experience, the months of rigorous rehearsals and dozens of performances ensured that the cast and crew were well prepared for the Dominion Drama Festival.

Although Lefty played for “comfortable” audiences as well as the working class in Vancouver, the crowd in Ottawa was the uppermost crust of the nation, and included Prime Minister Mackenzie King, former prime ministers RB Bennett and Robert Borden, Lady Tupper (wife of Sir Charles), and Governor General Lord Tweedsmuir. Surprisingly, considering that many of these people had led the charge against labour radicalism at some point in their careers, the play received a standing ovation and extended applause that coaxed the cast to return to the stage for a second bow. Lady Tupper, who was heavily involved with the Winnipeg Drama League, another contestant, was heard muttering “the God-damned hypocrites!” RB Bennett even hosted a tea-party for the cast at Government House.

Mackenzie King recorded his impression in his diary:

The labour play “Waiting for Lefty” while extreme, was a true picture of the hard life which men are encountering today, and the kind of thing which is bred therefrom. Parts of the play reminded me very much what I myself witnessed when dealing first hand with industrial disputes some years ago [as Minister of Labour].

H. Granville-Barker, the adjudicator, said Lefty “was quite obviously the most interesting thing of the evening,” and that the play signaled a “renaissance of the drama,” but ultimately awarded the trophy for best overall play to another social realist production entitled Twenty-five Cents, which he felt was more nuanced. Nevertheless, the Progressive Arts Club won for best English language play against some of the top theatre troupes in the country.

It’s difficult to interpret the positive reception Lefty received across class lines and by some of the Canadian Left’s most famous arch-enemies. Even Granville-Barker in his adjudication at the Ottawa festival said he found it ironic “that this most comfortable audience so frantically applauded the presentation of this play.” Perhaps because it was only a play despite its obvious ideological slant and therefore wasn’t perceived as a threat to the socio-political status quo. Possibly the authorities backed off their initial knee-jerk attempt to censor the play because they didn’t want to be seen as philistines obstructing a cultural renaissance. In any case, the story of this play shows a softening of establishment attitudes to the plight of the working class in the latter part of the depression to which Waiting for Lefty itself perhaps contributed.

As for the Progressive Arts Club, they produced about ten more plays, but were never able to repeat the success of Waiting for Lefty. The theatrical tradition they started in Vancouver however, remains a staple in the local theatre scene with echoes in the work of Headlines Theatre, Theatre in the Raw, and Vancouver Moving Theatre.